When you think about some of your favorite fantasy stories, their worlds likely jump to mind right away. Middle-earth, Narnia, Prydain, Oz, Westeros, and so many other fantastical places are as much central characters in their books as any of the humans and monsters that populate them.

It’s not surprising that a ton of work goes into building those worlds, from laying out their maps to creating their magic systems to determining their languages and currencies. This part of the creation process can become so involved that there’s a joke among fantasy writers that it’s hard to know when to stop worldbuilding and start writing.

Some writers take a deep dive into their worldbuilding and don’t stop until they’ve figured out every inch of their worlds and planned out thousands of years of history (looking at you, J.R.R. Tolkien), while others are content to start with a basic setting and develop the details as needed, while writing. My worldbuilding for Teshovar falls somewhere in the middle, in that I did take a lot of time to figure out how the world works, how it’s different from our world, and what’s important about its history, cultures, and ways. I didn’t go as far as fully developing a bunch of languages in advance, though, and I fully admit that I make up Aevash words on the fly and then make sure they make sense with what’s come before while I’m editing.

One area of the worldbuilding that readers have asked me about is how and why I chose the measurement systems that are used in Teshovar. If you’ve read either of my books, you likely saw characters referring to distances in miles, inches, and feet while talking about weights in pounds. I could have invented new systems of measure, or I could have had them use the metric system. My decision to go with the Imperial system was a choice I made after giving the implications a lot of thought.

Accessibility is extremely important to me in my writing. I’ve written before about how I name characters in ways that hopefully ensure that readers won’t mix up one person in a story with another. Even though it’s possible and likely that two characters with the same first name might bump into each other in a “real” Teshovar world, that could be confusing for a reader. It’s my job to tell you a good story, and part of that job is removing as many obstacles between you and your enjoyment of that story as I can.

Similarly, I could have characters measuring distances in flamgadrons and weights in rompadoolies, but that wouldn’t make any sense to you. Every time the book mentioned a measurement, you’d have to figure out what I meant. It’s much simpler to stick with a measuring system that already exists and is widely used. In the end, I chose to use the Imperial system just because I’m American, and that’s the system I’m most familiar with. I wish I could provide for fans of the much more sensible metric system at the same time, but the choice had to be made, and I went with the one I knew I could write most consistently and easily.

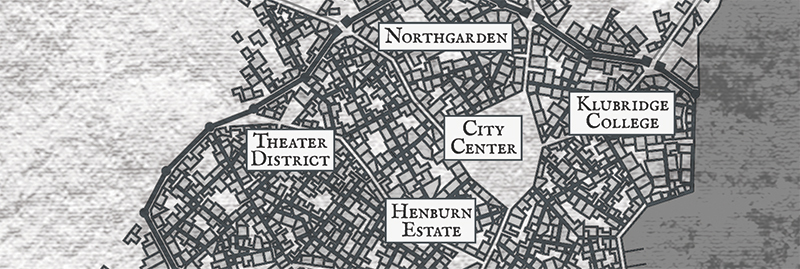

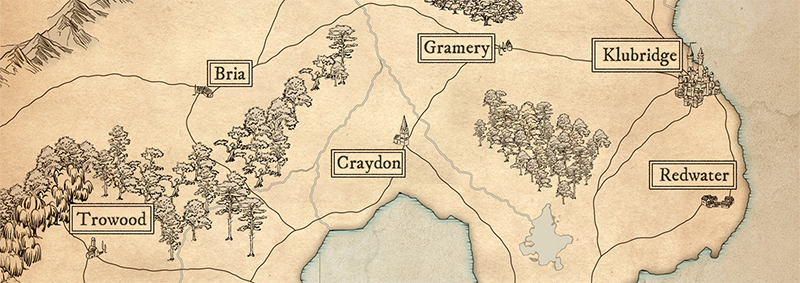

Similarly, the characters of Teshovar measure time in seconds, minutes, hours, days, months, years, decades, centuries, and millennia. Using those familiar units is much clearer and more accessible than saying it took twelve chimtywigs to travel from Klubridge to Aramore. I also refer to the seasons of the year as winter, spring, summer, and autumn or fall, and they come in the same order in Teshovar that they come in our world. And, again due to my living in North America, the weather that accompanies the seasons matches what I’m used to. In Teshovar, it’s warm in the summer and cold in the winter.

There absolutely is an argument to be made for the value of more immersive worldbuilding where the author painstakingly creates all these systems and units from scratch, and there is a place for that kind of writing. That’s just not the kind of writing I do. I want for you to be immersed in my world, but I also want you to be comfortable there and to feel like it’s a familiar place where you can pay more attention to the characters and their stories than you do to parsing and figuring out things that are already known and commonplace to the people who live in that world.

There’s already a lot of weird stuff in Teshovar that I’ve given you to learn– magic systems, political and military structures, unusually delineated class struggles, and so on! The last thing I want you to do is get stuck trying to decide how long a street is or what time a character showed up for dinner. Accessibility is key in my writing, and I hope to keep it that way.